Ospreys

Osprey frequency The Osprey has a wide distribution across the world: its huge nests are built along oceans, lakes, rivers and streams—almost anywhere there is a safe nesting, shallow water, and abundant fish.

The Osprey is easy to find around Kootenay Lake, which has one of the highest concentrations of breeding Ospreys in the province. About 20 to 30 pairs nest along the West Arm between Balfour and Nelson, albeit with considerable annual variation. Not only are Osprey pleantiful, but their nests are usually out in the open on the top of structures ranging from dead trees to pilings.

It seems likely that the present incidence of Ospreys in the region is similar to that of historical times. But, in the mid-twentieth century Osprey numbers were small. The problem seems to have been common across North America and has been attributed to pesticides. With pesticide controls in place, the numbers began climbing in the early 1970s and probably peaked in the late 80s. Two recent reports discusses the bird’s local status:

in 2000, Osprey of the West Kootenay;

in 2007, …nesting Ospreys in the West Kootenay….

Ospreys are the pride of the Lake.

As the pictures below reveal, the Osprey primarily eats fish which it catches live. This has also earned it the name, fish hawk; part of its scientific name, haliaetus, translates from the Greek as fish eagle.

Ospreys are migratory birds; they begin to arrive in the Kootenays in the first week of April, having wintered from Central America (such as Costa Rica) to northern South America (such as Venezuela). Males generally return a little earlier than females, but it isn’t long until courtship activities are underway. Pairs usually reclaim their previous nest site. At this time the sky-dance display may be observed: males in flight make repeated short dives in the air—sometimes from considerable heights—with legs dangling, and constantly utter their characteristic cry. Old nests are refurbished or new nests are built, the latter often taking place in response to the presence of an incubating Canada Goose at the original site.

On the West Arm, egg-laying begins in the last week of April for the earliest nesters. Most females lay during May. The eggs are incubated for about 39 days, primarily by the female, while the male does the hunting for the pair. Even after the eggs hatch, the male Osprey continues to provide all the food for the family. Most chicks hatch in June. Although the female still appears to be incubating eggs at this time, she may in fact be brooding tiny nestlings. Patient observation will eventually reveal when young are present, as the female will eventually stand up in the nest to feed morsels of fish to them.

Normally three chicks are hatched in a brood, but often only two are raised to fledging age. The amount of food provided to the family is the major factor determining how many young survive,

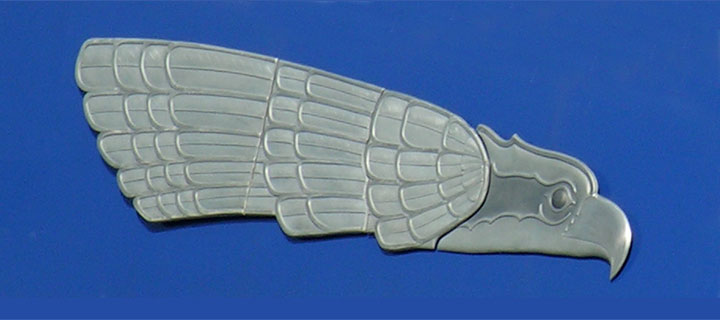

M.V. Osprey 2000 A representation of an Osprey from the hull of the M.V. Osprey 2000, the ferry which plies Kootenay Lake. Curiously, the bill is presented with an eagle’s heft, rather than an osprey’s (see image and caption below).

M.V. Osprey 2000 A representation of an Osprey from the hull of the M.V. Osprey 2000, the ferry which plies Kootenay Lake. Curiously, the bill is presented with an eagle’s heft, rather than an osprey’s (see image and caption below).

which in turn is influenced not only by fish abundance and availability, but by weather conditions or the hunting ability of individual males. The primary prey for Ospreys here are suckers. Other fish taken include Mountain Whitefish, Kokanee and Rainbow Trout.

Young Ospreys remain in the nest for about 55 days, but there is considerable variation in the age at which they fledge. Earliest broods fledge at the end of July, while some chicks are still in the nest at the beginning of September. Even after taking their first flight, Osprey chicks are often fed at the nest and families may hang around for several weeks.

In fall, adults are generally the first to head south, around mid-September. The last of the young stragglers are gone by the second week in October.

A juvenile, female Osprey stares into the camera.

A juvenile, female Osprey stares into the camera.

“Ospreys abounded along the river, their nests being...very large and invariably placed at the extreme top of a bare dead tree....”

“Ospreys abounded along the river, their nests being...very large and invariably placed at the extreme top of a bare dead tree....”

along the Upper Columbia, 1887

As with other raptors, the female osprey is larger than the male. Usually, the bird with a completely white breast (left) is male, while that with the motley necklace (right) is the female. In this case, the behaviour of the pair was consistent with this.

As with other raptors, the female osprey is larger than the male. Usually, the bird with a completely white breast (left) is male, while that with the motley necklace (right) is the female. In this case, the behaviour of the pair was consistent with this.

Osprey coitus The males arrive at the Lake in early April and the females follow within a few weeks. Then breeding begins. From start to finish, copulation lasts only about ten seconds.

Osprey coitus The males arrive at the Lake in early April and the females follow within a few weeks. Then breeding begins. From start to finish, copulation lasts only about ten seconds.  Catherine Aitken

Catherine Aitken

An Osprey mother seems to be wrapping a wing around its recently born chick.

An Osprey mother seems to be wrapping a wing around its recently born chick.  Catherine Aitken

Catherine Aitken

Ospreys usually mate for life. By early May they begin a five–month partnership to raise their young.

Ospreys usually mate for life. By early May they begin a five–month partnership to raise their young.

The Osprey feeds on fish which it catches live. It then adjusts the fish into an aerodynamic position (head first) to carry it home.

The Osprey feeds on fish which it catches live. It then adjusts the fish into an aerodynamic position (head first) to carry it home.

An Osprey lifts its tail and defecates. This lightens the load before flying.

An Osprey lifts its tail and defecates. This lightens the load before flying.

Many of the Osprey’s nests are on man–made structures near or on the Lake—but not all are. This one is at the top of a broken tree trunk.

Many of the Osprey’s nests are on man–made structures near or on the Lake—but not all are. This one is at the top of a broken tree trunk.

The Osprey is a raptor. As with all raptors, the hooked bill is used for ripping food—in the osprey’s case, fish. Not only is the osprey a smaller bird than an eagle, insert, but its bill is also smaller relative its head.

The Osprey is a raptor. As with all raptors, the hooked bill is used for ripping food—in the osprey’s case, fish. Not only is the osprey a smaller bird than an eagle, insert, but its bill is also smaller relative its head.

With its wings and tail spread to slow it down, the Osprey lowers its legs and tips its head down to watch its landing on the nest.

With its wings and tail spread to slow it down, the Osprey lowers its legs and tips its head down to watch its landing on the nest.

An Osprey raises its wings and lifts off from its nest.

An Osprey raises its wings and lifts off from its nest.

An Osprey generally fishes in the calm of the early morning or evening. At that time, the water is usually smoother and the birds can more readily see into the Lake.

An Osprey generally fishes in the calm of the early morning or evening. At that time, the water is usually smoother and the birds can more readily see into the Lake.

An adult has yellow eyes.

An adult has yellow eyes.

By the time they fledge, Osprey chicks are as large as adults. Yet, they are distinguishable. A chick’s eyes are orangish, rather than the yellow of the adults, and their feathers are tipped in white as if they had been dipped in cream. Contrast these eyes and feathers with those of the adults on this page. This picture was taken in early August.

By the time they fledge, Osprey chicks are as large as adults. Yet, they are distinguishable. A chick’s eyes are orangish, rather than the yellow of the adults, and their feathers are tipped in white as if they had been dipped in cream. Contrast these eyes and feathers with those of the adults on this page. This picture was taken in early August.

This male Osprey has not taken its catch back to its nest, but rather has stopped at an old piling along the way to feast. While holding the fish with one of its claws, the bird started at the head and gradually proceeded to the tail, occasionally throwing the less tasty bits back into the Lake.

This male Osprey has not taken its catch back to its nest, but rather has stopped at an old piling along the way to feast. While holding the fish with one of its claws, the bird started at the head and gradually proceeded to the tail, occasionally throwing the less tasty bits back into the Lake.

The first step in learning to fly for an Osprey chick is to face into the wind and spread the wings.

The first step in learning to fly for an Osprey chick is to face into the wind and spread the wings.

A male Osprey stops for breakfast after catching a sucker at sunrise.

A male Osprey stops for breakfast after catching a sucker at sunrise.

The orange eyes and white-tipped feathers of this Osprey reveal it to be a chick.

The orange eyes and white-tipped feathers of this Osprey reveal it to be a chick.

This female Osprey chick is clearly suffering a bad hair day.

This female Osprey chick is clearly suffering a bad hair day.

If there is a time when man envies the birds, it surely is when they are soaring.

If there is a time when man envies the birds, it surely is when they are soaring.

This osprey is carrying a headless fish. An osprey will often stop for a nibble after catching a fish; the fish is eaten head first. Note the one–leg technique.

This osprey is carrying a headless fish. An osprey will often stop for a nibble after catching a fish; the fish is eaten head first. Note the one–leg technique.

The underside of the Osprey’s wing shows a distinctive dark area at the wrist (the bend of the wing).

The underside of the Osprey’s wing shows a distinctive dark area at the wrist (the bend of the wing).

At the end of a downstroke, this Osprey seems to fly past Mount Sphinx in the Purcells.

At the end of a downstroke, this Osprey seems to fly past Mount Sphinx in the Purcells.

A female Osprey flies down the West Arm.

A female Osprey flies down the West Arm.

A sunny day, a commanding view, a tasty fish, no eagles in sight—life can be good.

A sunny day, a commanding view, a tasty fish, no eagles in sight—life can be good.

Information from Wikipedia: Osprey. Information from Jim Rible: Osprey.

![]()