Sand points

Ecological Reserves British Columbia’s Ecological Reserve Act has a provision to reserve Crown Land if it contains unique and rare examples of geological phenomena (see, Park Designations). Leaving aside the inept use of the word, unique, in the Act, the sand points of the West Arm would seem to qualify. Some of the points are adjacent to, but outside, the West Arm Provincial Park.

The sand points of the West Arm of Kootenay Lake extend into the current nearly at right angles to the shoreline. This makes them unusual—and I mean really, really, unusual. Most sand spits in the world lie more or less parallel to the shore.

A few questions emerge:

What evidence suggests the sand points are unusual?

What evidence suggests the sand points are unusual?

What conditions seem necessary for their formation?

What conditions seem necessary for their formation?

What is the explanation for them?

What is the explanation for them?

Evidence

Until recently, I had no reason to suspect that the sand points of the West Arm were atypical. I spent childhood summers at my grandparents’ log cottage across the Lake from the Five-Mile Point and would row, paddle, and even swim over to it. For my cousins and me, this sand point was merely a particularly pleasant part of our playground. It wasn’t until I returned to the Lake in retirement and sought a better understand of my surroundings, that I came to suspect that the point was unusual.

To acquire some understanding, I had assembled a number of books on beaches (see bibliography) and soon discovered that none explicitly treated such points. Granted, sand spits were discussed, but spits lie more or less parallel to a coast, as can be seen in the sand spits on the east sides of both Kokanee Creek Park and the Harrop peninsula, each of which encloses small lagoons.

The Five-Mile Point is unusual in that it is both narrow and extends at right angles to the shore out into current.

The Five-Mile Point is unusual in that it is both narrow and extends at right angles to the shore out into current.

Why had authors not discussed the formation of sharp points of sand extending at right angles to the coast? Were the points just too rare to have been considered? I had no way to explore the possible rarity of the points until the advent of Google Earth. This amazing (free) program allows a detailed navigation of the whole Earth. I looked at the sand points of the West Arm (below), and then looked for comparable features on scores of other lakes worldwide. A few others can be seen (Okanagan Lake, north of Carrs Landing; Little Shuswap Lake), but they were not as well formed as those on the West Arm. While, I haven’t been exhaustive, my searches reveal our sand points to be remarkably unusual. Note: one is looking for a totally sandy point, not a point of land with a beach around the edges; nor is one looking for a sand delta dumped directly off the mouth of a creek. (Incidentally, there are spectacular sand points on a lagoon on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, but apparently they arise from an entirely different mechanism than do the West Arm points).

Conditions

This list of conditions is somewhat speculative. It is based partly upon observations and partly upon my tentative explanation of the points. None of these items seems to be sufficient by itself; all must be present for a sand point to form.

The Seven-Mile Point is the smallest of the three major sand points between Nelson and the Nine-Mile Narrows, but it has all the right features: its narrow and extends at right angles to the shore.

The Seven-Mile Point is the smallest of the three major sand points between Nelson and the Nine-Mile Narrows, but it has all the right features: its narrow and extends at right angles to the shore.

The lake should:

have a ready source of sand;

have a ready source of sand;

be narrow and elongated;

be narrow and elongated;

be closely confined by steep mountains on either side;

be closely confined by steep mountains on either side;

be relatively shallow;

be relatively shallow;

not have too strong a current.

not have too strong a current.

The availability of sand, while necessary, is obviously insufficient for points; many lakes have sandy beaches, but few have points. Further, many lakes are narrow and long—our Main Lake, Slocan Lake, Finger Lakes (N.Y.)—but they don’t have sand points. A lake closely confined by steep mountains is not unusual, but such a lake is usually also deep—Main Lake, Slocan Lake. The West Arm is unusual in having steep mountain sides, but also being fairly shallow. A strong current could erode a point: it is striking that points have not formed in any of the narrows farther east on the Arm. It may be important that the point extends from the end of a peninsula, as they do on the West Arm, but, as yet, it is unclear in my mind whether this is necessary or just a consequence of creeks depositing material in a shallow lake. It may also be the case that the annual cycle of high and low water plays a role in building the points by changing the location of deposition.

Cross-valley winds The steep valley walls substantually confine the movement of air over the surface of the water to be along the lake’s axis, either up the lake (towards Balfour) or down the lake (towards Nelson). But, there are some cross-lake winds. The drainage (katabatic) winds of a clear night flow down the mountain slopes and offshore, but these are so gentle as to merely ripple the water, and don’t extend far out over the water. Much more vigorous are the thunderstorm downdrafts which sweep down the bigger lateral valleys such as that of Duhamel Creek. And although waves from these winds would only serve to enhance the sand point associated with that creek, such winds don’t seem very important.

Explanation

Each of the sand points on the West Arm has a creek within a few hundred meters which provides a ready source of sand. Waves move the sand from creek mouth to sand point by the mechanism of longshore drift. This same sand moving mechanism serves to create both the sand points (extending nearly at right angles to the shore) and sand spits (lying nearly parallel to the shore). Leaving aside boat wakes, waves are generated by the surface wind. In a steep-sided and narrow valley, substantial winds normally only blow along the valley, and so the majority of the big waves also run more or less along the axis of the lake. And, therein lies the clue to the formation of sand points rather than sand spits. At Five-Mile Point, for example, waves moving up the lake move creek sand towards the east; waves moving down the lake push it west; it piles up in the middle to form a point; there are scant waves moving across the lake to push the sand back towards the shore. On most bodies of water, where the winds are unconstrained by a canyon of mountains, the dominant waves move toward the shore and only a smaller component of them moves sand along the shore—the result then is a sand spit nearly parallel to the shore. But, usually a canyon of mountains accompanies deep water (the Main Lake, Slocan Lake, many coastal fiords) and now any sand that moves offshore is quickly lost to the depths without the possibility of forming a point. Further, if the current is high (such as in the narrows on the eastern half of the West Arm), sand that might otherwise have formed a point is just washed downstream.

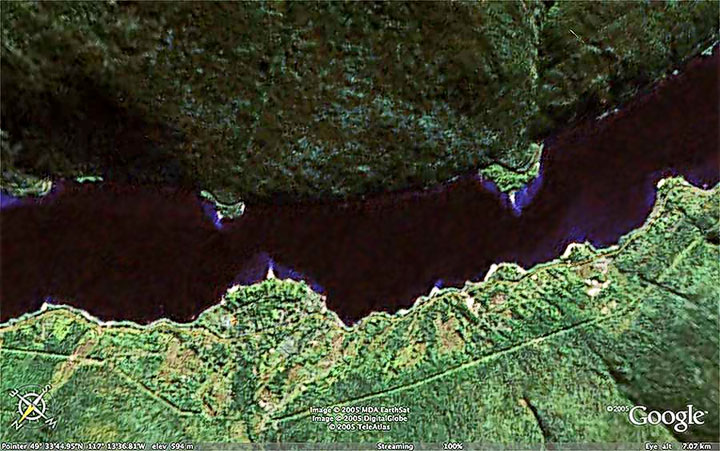

The sand points of the West Arm as if viewed looking straight down from an altitude of seven kilometers. The Five-Mile Point is on the right, the Six-Mile Point (Duhamel) is middle left; the Seven-Mile Point (Tunstall) is on the left. These points are distincly unusual in that they are narrow, sharp, and stick out into the Lake at right angles to the shore.

The sand points of the West Arm as if viewed looking straight down from an altitude of seven kilometers. The Five-Mile Point is on the right, the Six-Mile Point (Duhamel) is middle left; the Seven-Mile Point (Tunstall) is on the left. These points are distincly unusual in that they are narrow, sharp, and stick out into the Lake at right angles to the shore.

This is an oblique view of the West Arm of Kootenay Lake looking east as if seen from an altitude of about seven kilometers. The bridge at Nelson is on the lower right and a bit of the Main Lake is seen in the upper left. The substantial mountains bounding the Arm confine most of the winds and thus the waves to move more or less along the axis of the Arm. The three major sand points are seen in the lower centre of the picture, but comparable points do not appear farther east.

This is an oblique view of the West Arm of Kootenay Lake looking east as if seen from an altitude of about seven kilometers. The bridge at Nelson is on the lower right and a bit of the Main Lake is seen in the upper left. The substantial mountains bounding the Arm confine most of the winds and thus the waves to move more or less along the axis of the Arm. The three major sand points are seen in the lower centre of the picture, but comparable points do not appear farther east.

I greatly appreciated the counsel of Professor Paul Komar (author of the university textbook, Beach Processes and Sedimentation) during the development of this material.

The use of the images from Google Earth on this Website is in accordance with Google’s policy.

![]()