Kokanee

(landlocked Sockeye Salmon)

As the glacier retreated from this area ten to twelve thousand years ago, large lakes of meltwater formed at the terminus and vigourous rivers flowed from them to the ocean. The rivers provided a path for Sockeye Salmon to move from the Pacific Ocean into the lakes; these salmon were the ancestors of the Kokanee. With the passing of the glaciers, the lakes shrank to their present size, and river levels fell with the result that the path to the ocean often became impassible. This was the case for the newly landlocked Salmon of Kootenay Lake, which adapted to their new life as Kokanee.

For those (the many) who are neither fishermen nor divers, the best time to see the Kokanee is from mid-August through September for that is when they crowd local creeks while spawning. And although non-spawning Kokanee have bright silver sides and a dark grey to blue back, the spawning kokanee turn crimson with a green to black head. The males develop long jaws, hooked snouts, and large teeth and a slight hump forms behind their heads. The spawning females retain their non-spawning shape and are not quite as colourful as the males.

Enter the underwater world of the Kokanee. This picture shows the scene both above and below the surface of the spawning creek. The male kokanee looks stunningly colourful. The red body and green head are characteristics of the spawning fish, but the yellows and blues are prismatic colours produced by light passing through the waves on the water surface.

Enter the underwater world of the Kokanee. This picture shows the scene both above and below the surface of the spawning creek. The male kokanee looks stunningly colourful. The red body and green head are characteristics of the spawning fish, but the yellows and blues are prismatic colours produced by light passing through the waves on the water surface.

In August, the Kokanee begin to move upstream in substantial numbers. The males are larger and have a somewhat humped back. The red of the kokanee is reflected off the underside of the water surface.

In August, the Kokanee begin to move upstream in substantial numbers. The males are larger and have a somewhat humped back. The red of the kokanee is reflected off the underside of the water surface.

A male (back) and female (front) swim side by side. During spawning, the male acquires a humped back, a hooked jaw and teeth.

A male (back) and female (front) swim side by side. During spawning, the male acquires a humped back, a hooked jaw and teeth.

More evident in this picture are the teeth the male has developed. They are used in combat against other males for good mates and spawning locations.

More evident in this picture are the teeth the male has developed. They are used in combat against other males for good mates and spawning locations.

This shot, from above the water’s surface shows one male biting the tail of another, presumably in an attempt to drive him off.

This shot, from above the water’s surface shows one male biting the tail of another, presumably in an attempt to drive him off.

This underwater shot shows one male (on the right) attacking another from below. The victim is thrashing about near the surface and in the process becomes engulfed in myriad bubbles.

This underwater shot shows one male (on the right) attacking another from below. The victim is thrashing about near the surface and in the process becomes engulfed in myriad bubbles.

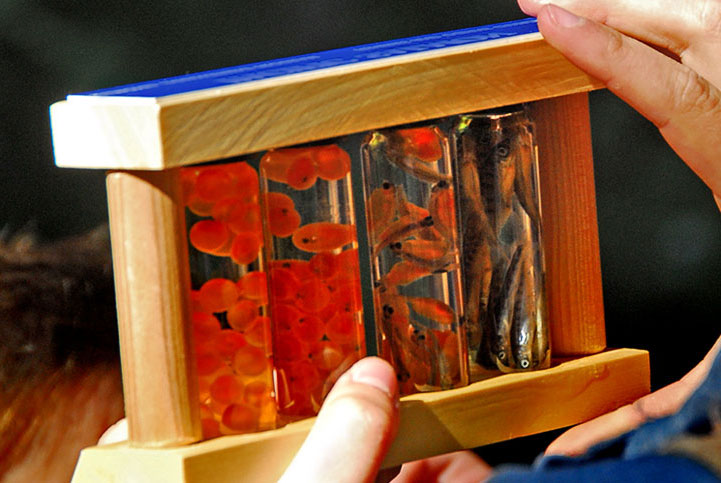

A guide at the Kokanee Creek Provincial Park shows visitors the development of the kokanee extending from eggs (left) through alevins, to fry (right).

A guide at the Kokanee Creek Provincial Park shows visitors the development of the kokanee extending from eggs (left) through alevins, to fry (right).

A kokanee fry (first year) swims by the shoreline. The spots on its side, parr marks, are characteristic of all salmonid young and can identify the species.

A kokanee fry (first year) swims by the shoreline. The spots on its side, parr marks, are characteristic of all salmonid young and can identify the species.

Another view extending from above the water’s surface to the fish below.

Another view extending from above the water’s surface to the fish below.

Fish, each driven by the same instinct, behave the same way and cluster together.

Fish, each driven by the same instinct, behave the same way and cluster together.

A shoal of female kokanee hangs motionless.

A shoal of female kokanee hangs motionless.

Male and female kokanee show a range of colours as they enter the creek to spawn.

Male and female kokanee show a range of colours as they enter the creek to spawn.

There isn’t much room to manoeuvre when many kokanee crowd into a shallow stream.

There isn’t much room to manoeuvre when many kokanee crowd into a shallow stream.

Even the jump over a barrier can get crowded

Even the jump over a barrier can get crowded

The kokanee is a salmon; it is prepared to jump over a barrier when it needs to.

The kokanee is a salmon; it is prepared to jump over a barrier when it needs to.

It is October and dead Kokanee litter the creek bed: they spawn, they die.

It is October and dead Kokanee litter the creek bed: they spawn, they die.

A Grizzly cub is eating a dead Kokanee it picked from the stream.

A Grizzly cub is eating a dead Kokanee it picked from the stream.

A Grizzly sow and her cubs have come to a spawning stream to feast upon Kokanee.

A Grizzly sow and her cubs have come to a spawning stream to feast upon Kokanee.

Information from BC Ministry of the Environment: Kokanee. There is also an informative article on the kokanee of Kootenay Lake in the wetlander, June 2005 (the newsletter of the Creston Wildlife Management Area). It discusses both the ecology and history of the fish.

![]()